HDR photography is a love-it-or-hate-it topic for many photographers. Some adore the detail it brings to a tricky scene, while others can’t stand the overprocessed look. The truth is, HDR can be a powerful tool — but only in the right circumstances. In this article, I’ll walk you through when HDR can truly help your photography, and when it will just make your images look worse.

Should You HDR or Not?

That’s the million-dollar question.

HDR photography has been through fads, from the “wow, look at all that detail” phase, to the “oh no, my eyes hurt” overprocessed phase. These days, most photographers (and viewers) prefer a realistic look — detail in both highlights and shadows, but with shadows and highlights still present.

There is a time and place for HDR, and also times when it does more harm than good. This guide will help you decide when to embrace HDR and when to run far, far away from it.

What is HDR Photography, Really?

HDR stands for High Dynamic Range — a fancy way of saying “there’s more contrast between light and dark than your camera can handle in one shot.”

It’s not actually a technique in itself — it describes the range of light in a scene. But over time, “HDR” has become shorthand for a certain processing workflow (and sometimes a very specific, very crunchy look).

In reality, HDR photography is about tone manipulation — capturing all the important tonal information in a scene through bracketed exposures and combining them later so you can adjust shadows and highlights without losing detail.

Ansel Adams was doing HDR long before Lightroom was a twinkle in Adobe’s eye. His Zone System was a film-era way to control and compress tonal range so both bright skies and dark shadows printed with detail.

In digital, that’s exactly what HDR software and Lightroom’s Merge to HDR tool do — they let you manipulate tones to fit more of the scene into your final image.

If you need the how-to on bracketing and merging, check out:

- HDR Photography Course — Camera Settings & Bracketing

- Guide to Merge to HDR in Lightroom

- 10 Tips on How to Do HDR Photos Without a Tripod

This article focuses on when to use HDR — and when to avoid it.

5 Situations When NOT to Use HDR Photography

1. Low-Contrast Scenes

If your scene fits comfortably within your camera’s dynamic range, HDR won’t help — it’ll just flatten your image and make it look fake.

How to check? Look at your histogram. If the graph doesn’t touch the far left (shadows) or far right (highlights), you have room to process a single RAW without losing detail.

Apply HDR here and you risk ending up with this:

Instead, process normally for natural contrast:

2. Silhouettes and Sunsets

This is the antithesis of HDR.

Silhouettes work because of deep, shadowed shapes against a brighter background. HDR would ruin that clean contrast by pulling detail into the dark areas — exactly what you don’t want.

For more on sunsets, read: 3 Tips for Creating Spectacular Sunset Photos.

3. Removing All Shadows

HDR is often abused to erase shadows entirely, but shadows are what give images depth, shape, and mood. Remove them, and everything looks flat.

Another example:

Even with colorful subjects, good blacks make colors punchier without oversaturation.

4. Trying to “Fix” a Bad Photo

HDR won’t rescue bad lighting, poor composition, or a boring subject. You’ll just end up with a technically detailed version of a still-boring photo.

5. People or Animals

Skin tones often look odd in HDR, and movement between bracketed shots causes “ghosting” — which software can sometimes fix, but not always gracefully.

The same applies to animals:

When HDR Works Best

HDR photography is best used when the contrast of the scene exceeds your camera’s dynamic range. If you’ve tried to expose for the highlights and the shadows are pure black, or expose for the shadows and the highlights blow out completely, your camera simply can’t capture the full tonal range in one shot.

This is where HDR really shines — capturing detail at both ends of the tonal scale and giving you the ability to balance the scene in post-processing.

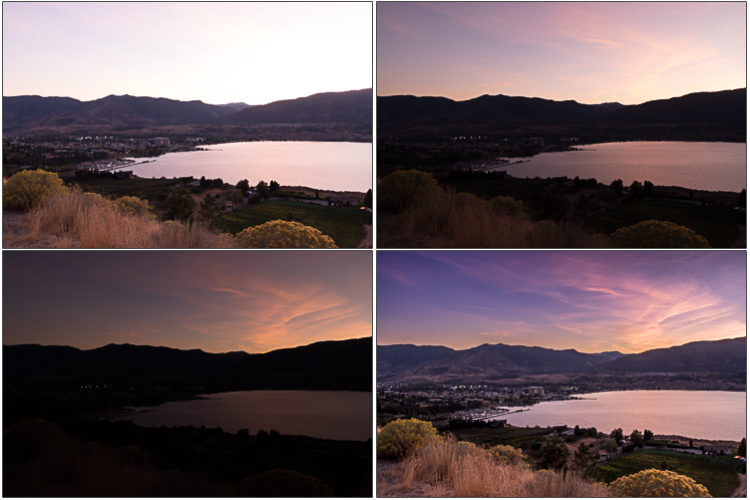

Here are three before-and-after examples so you can see exactly when HDR makes sense.

I needed four shots, each 2-stops apart, to capture the full range of tones in this high contrast scene.

Finished HDR image, merged and processed entirely in Lightroom.

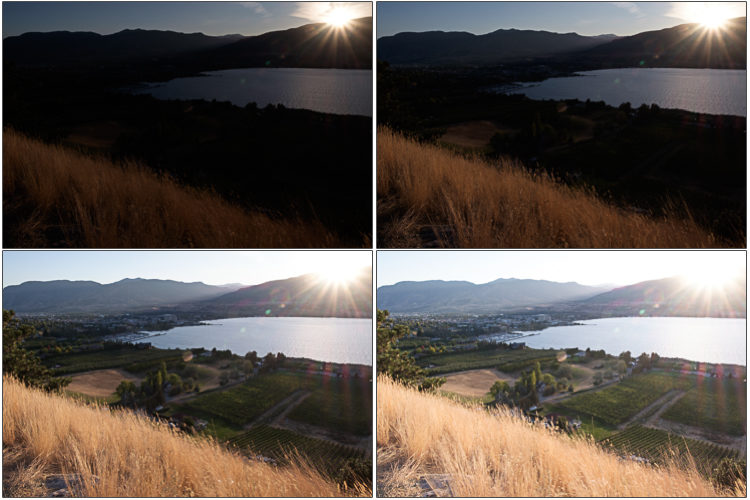

Another High Contrast Example

Three hand-held bracketed images and the processed image.

Notice anything different here? After debating, I flipped the final processed image horizontally so your eye follows the rows of vines into the image — not out of it.

This is a composition decision you can make later, and it’s a subtle change that helps the viewer’s eye stay inside the frame.

Blue Hour HDR Example

Three bracketed images (shot on tripod) and processed version.

Final HDR image retaining detail in the lit building, sky, and shadowed areas.

HDR as a Tool, Not a Default Setting

You may have noticed that in this article, the “When NOT to use HDR” list is much longer than the “When to use HDR” one.

That’s not an accident.

HDR is a specialty tool. Use it deliberately when the scene demands it, not as your default for every shot.

Common HDR Mistakes to Avoid

- Overprocessing: Too much tone mapping leads to halos, gray skies, and muddy colors.

- Ignoring composition: HDR can’t fix poor framing or a lack of subject interest.

- Forgetting shadows are your friend: Removing all contrast flattens your image.

- Not bracketing enough shots: Up to 5 well-exposed frames at 2-stop intervals might be needed.

- Brackets not far enough apart: If you bracket 1 stop apart and take 5 images you get a range from -2 to +2. If you bracket 2 stops apart and take 5 frames, you get -4 to +4. That makes a big difference when the range of contrast is high.

- HDR for moving subjects: Unless you’re going for artistic ghosting, it’s best avoided.

Master the Art of Knowing When to Use HDR

HDR can transform the right scene into a masterpiece — but knowing when to use it is key.

Learn the complete process, from identifying the perfect HDR scenarios to editing for natural results, in our HDR Photography Course.

FAQs About When to Use HDR

What is HDR best used for?

HDR is best for high-contrast scenes where your camera cannot capture detail in both shadows and highlights in a single shot. It’s ideal for landscapes, interiors with bright windows, or dramatic skies, preserving tonal detail across the entire range.

When should I shoot in HDR?

Shoot in HDR when the scene’s dynamic range exceeds your camera’s sensor capabilities. Typical cases include sunrise or sunset landscapes, architecture with bright skies, or interiors with mixed lighting. Always bracket exposures to ensure you capture every tonal detail.

Do professional photographers use HDR?

Yes, professional photographers use HDR when it enhances their work. Pros typically apply HDR subtly, aiming for natural results that maintain depth and contrast while recovering detail in shadows and highlights without the “overprocessed” look.

What are the disadvantages of HDR?

HDR can create unnatural colors, halos, or flattened contrast if overdone. It may also produce ghosting with moving subjects and requires more time in post-processing. Poor use of HDR can make images look artificial or lifeless.

How do I know if my scene needs HDR?

Check your histogram. If the graph touches both ends and shows clipping in highlights or shadows, HDR can help capture the full dynamic range, preserving detail in bright skies and deep shadows.

Can I use HDR for sunsets?

Usually no. Sunsets often benefit from natural contrast and silhouettes, which HDR processing can flatten. Expose for the sky to retain rich colors, letting foregrounds go dark for dramatic effect.

Final Thoughts

You’ve probably noticed there are more reasons to avoid HDR than to use it. That’s because HDR should be a conscious choice, not a default setting. When it fits the scene — like high-contrast interiors, backlit landscapes, or tricky architectural shots — it can elevate your work. When it doesn’t, it can ruin an otherwise strong image.

HDR can transform the right scene into a masterpiece — but knowing when to use it is the real skill.

Cheers,